Was James Ripley Really Such an Idiot?

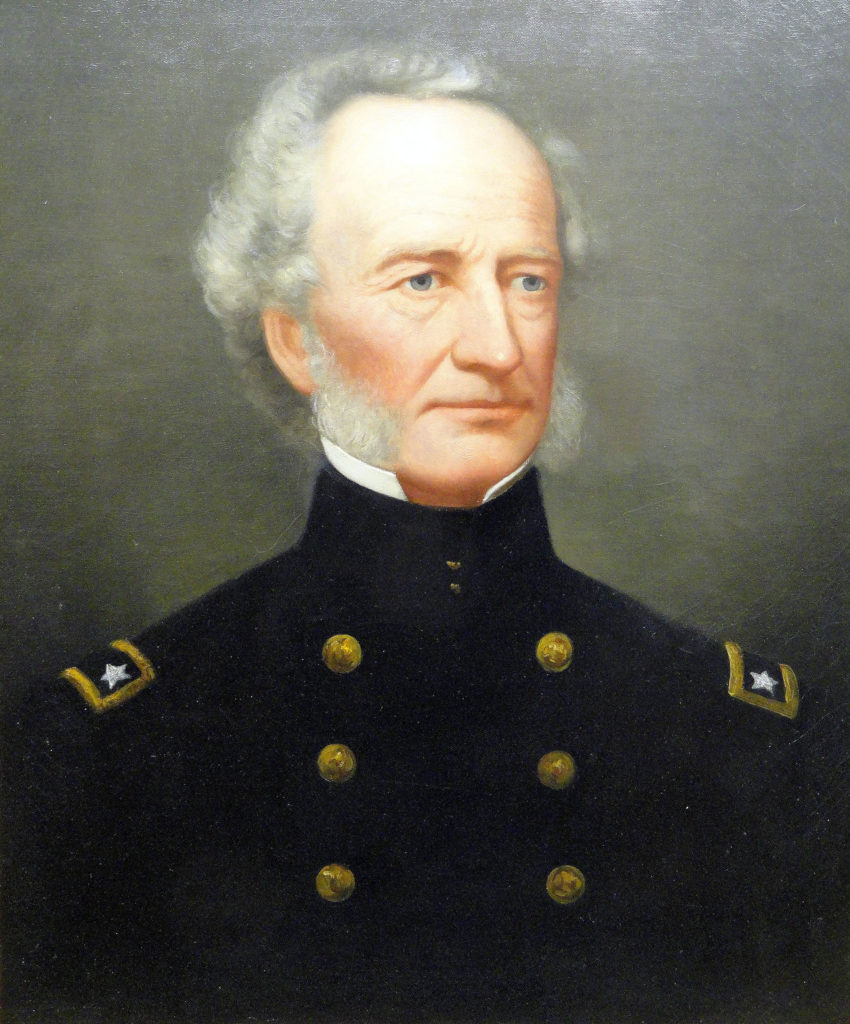

Ever since I was a little boy, I’ve been hearing collectors heap abuse on James Wolfe Ripley, the Union’s Chief of Ordnance during the initial years of the Civil War. People really don’t like this guy…and he’s been dead since 1870!

The reasons why Ripley is so unpopular today are kind of difficult to fathom. It’s not like he was a war criminal, a traitor or some sort of disastrous field commander. All he really did to attract so much negative attention is resist the wide-scale adoption of repeating longarms. Should this really be enough to get people all “up in arms” over 150 years later? I don’t think so…

Where Did All This Hatred Come From?

At the root of this problem is that most gun books are written by antique arms enthusiasts, and many of those authors are emotionally attached to the very weapons that Ripley thought were too complex or innovative for practical warfare and immediate need. If you are a huge fan of the Spencer rifle, for instance, and you know that Ripley was fairly conservative when it came to adopting those repeaters, then I guess it isn’t such a big leap to jump to the assumption that “Ripley was an idiot!” What is easy to forget in hindsight is that the Spencers that were issued had lots of performance and ammunition issues in the field. It was a very well-thought-out system that simply wasn’t ready for general issue.

So Who Was This Guy, Anyway?

Born on December 10, 1794, James W. Ripley was fairly old to be a serving officer in the Civil War. This has been seen by many as proof that he was behind the times. But the exact opposite was true. His knowledge was so extensive, and his experience with modern weapons systems so advanced, that he was considered absolutely indispensable by even the most accomplished of his peers. A West Point graduate, he was already a veteran with considerable field experience when he was appointed superintendent of the Springfield Armory in 1842, a post he held until 1854. Aside from his considerable administrative accomplishments, it is often forgotten that he had a very hands-on involvement in the development of the Model of 1855 series of firearms, one of the most effective battle weapons in the War Between the States.

When Confederate forces attacked Ft. Sumter in April of 1861, Ripley was almost immediately ordered to Washington to take over as Chief of Ordnance. It was literally a case of “this is a full-blown emergency…call Ripley!” At 66-years old, Ripley was initially reluctant to accept the position, but his colleagues (just about all of whom admired and respected him) insisted that he was the only man for the job.

And true to the criticisms levelled at him today, Ripley did indeed prioritize getting serviceable muzzleloading rifle-muskets into the hands of the troops over experimenting with or adopting new firearms that did not have a record of reliable performance in the field. It is not that he was uniformly against testing and issuing innovative firearms. He did plenty of that. Just about every researcher who specializes in Ordnance Department records will tell you that when breechloaders and breechloading repeaters could be made in reasonable numbers, and had shown themselves to be reliable and able to endure the rigors of service, Ripley endorsed them.

Ripley just thought that given the extreme demands of the crisis he should concentrate most of his efforts on arming the vast number of troops then in service with guns known to work and for which he was sure he could supply plenty of reliable ammunition. In fact, the Chiefs of Ordnance who came after him never fully altered from this path, proving that he was far from being some sort of doddering old fool who stupidly stood alone in his resistance to change. If he was such a stubborn, old-fashioned freak then how do you explain the fact that single-shot longarms remained the standard weapon of the U.S. infantryman until the adoption of the Krag in 1892? That’s right — 1892!

The Basics of My Argument

The Army (not to mention the Navy, which had it even worse) was already overwhelmed by the logistical challenge of acquiring and distributing the wide variety of calibers and cartridge configurations then in the field. Would making matters even worse have been a good idea? And some of the most promising breechloaders and repeaters used cartridges that were either known to be unreliable or were difficult to procure. In fact, the machinery to manufacture large numbers of cartridges for many of these weapons hadn’t even been invented yet! And let’s not even get started on the scarcity of machine tools. There wasn’t enough machinery being produced to equip the manufacturers of standard-issue muskets. Devoting the extremely limited resources of the American tool and die industry to unproven new ideas was a gamble that Ripley simply could not afford to take.

And then there is the matter of training. As readers of an excellent new article by Charlie Pate in the August 2018 issue of our magazine (Man at Arms for the Gun and Sword Collector) will learn, our soldiers were already having enough problems operating the traditional longarms with which they were already familiar. In the heat of battle, complexity is not necessarily your friend. Not to mention the matter of tactics. The officers of the day were employing strategies that were often too antiquated for even the Minié ball. That’s why the buck-and-ball load turned out to be so darned effective. If you can’t take full advantage of your new equipment, and it might malfunction anyway, proven standbys start to make a whole lot more sense.

Other Objections to Ripley

While it is less often mentioned today, what Ripley was criticized for the most during his own lifetime was the chaotic procurement system employed during the initial months of the war, which led to the purchase of many substandard arms and to the signing of contracts with several manufacturers who never made satisfactory deliveries. This situation is well documented in our book Civil War Arms Makers and Their Contracts, which is a facsimile reprint of the 1862 Report by the Commission on Ordnance and Ordnance Stores, and makes much more fascinating reading than its title might initially suggest.

This critique is even more easily answered than the first one. The Union was suddenly and unexpectedly at war. Thousands of new recruits needed guns right away, and hardly any standardized models were available. If these young men were going to fight with something other than pitchforks and pikes, they would have to make do with whatever could be acquired immediately on the open market. That’s what needed to be done. There was literally no other option. What else was he supposed to do?

A Legacy to Stand By

So please, let’s put a lid on the Ripley hatred. He just doesn’t deserve it. Ripley seems to have been an exceptionally honest and capable officer who stood up to a shocking amount of political meddling, managed his department with remarkable efficiency under unprecedented circumstances, and put a steady stream of arms into the hands of the troops. These guns worked and got the job done. That’s a legacy to stand by.

Thanks for this article. I have thought this for a long time, but never followed it up. I am in full agreement.

Let’s hope your informative article will set the record straight and the haters will shift their opinion to one of respect for a man that did his job to the best of his ability and did it well during those trying times for our nation. He just doesn’t deserve the disrespect without the facts.